In her stunning essay “On Excellence,” Cynthia Ozick pays tribute to her mother, a woman with a big heart and many gifts and passions. Ozick recalls how her mother used to make her laugh, for she was “so varied, like a tree on which lemons, pomegranates, and prickly pears absurdly all hang together,” and she suggests this singularly wonderful parent epitomized excellence, “insofar as excellence means ripe generosity.”

In her stunning essay “On Excellence,” Cynthia Ozick pays tribute to her mother, a woman with a big heart and many gifts and passions. Ozick recalls how her mother used to make her laugh, for she was “so varied, like a tree on which lemons, pomegranates, and prickly pears absurdly all hang together,” and she suggests this singularly wonderful parent epitomized excellence, “insofar as excellence means ripe generosity.”

When I think of my friend Diane Gottlieb, Ozick’s definition of excellence comes to mind. Certainly, Diane is a talented writer and editor. Her flash fiction, essays, and poems have appeared in several journals, and she is the prose and nonfiction editor of Emerge Literary Journal and a reviews team member for Hippocampus Magazine. But what I admire most about Diane is her “ripe generosity.” She fosters connections in the literary community, supports others’ creative endeavors, celebrates their achievements, models kindness, care, and interest, and gives and gives and gives.

I suppose there are more patent ways to elucidate human excellence, but honestly, the older I get, the more I appreciate Ozick’s definition. In manifesting “ripe generosity,” Diane Gottlieb and others like her make the world a better place. I don’t think anything can surpass that achievement. Or can possibly matter more.

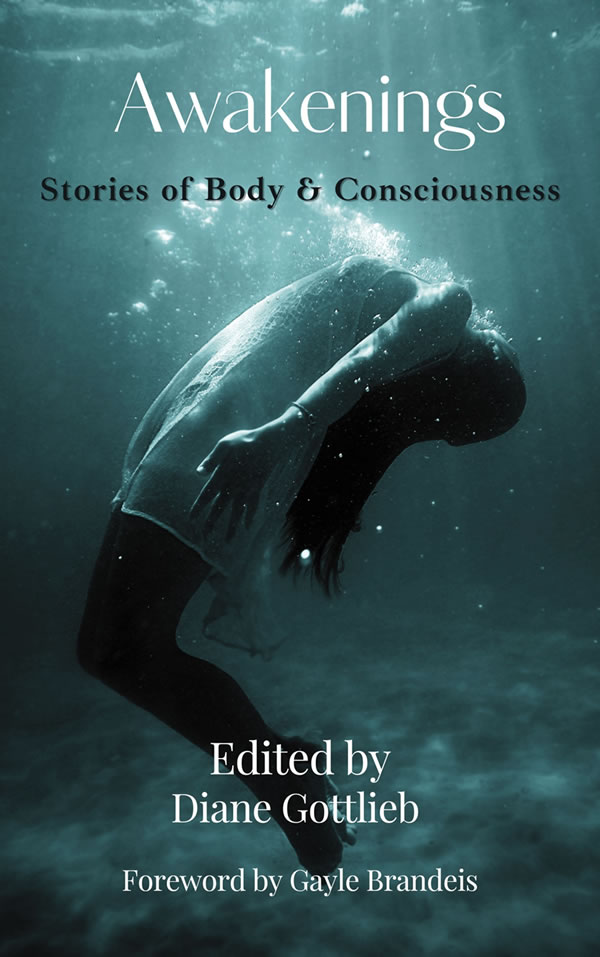

Writing can also be a giving act, and it is the editors who orchestrate this sharing. Most recently, Diane Gottlieb has edited Awakenings: Stories of Body & Consciousness (ELJ Editions, October 2023), an anthology of short essays about the body. I have a flash in Awakenings and was given the lovely opportunity to read an advanced copy. What a remarkable compilation. I’m so touched Diane was willing to let me ask her some questions about Awakenings. Our conversation follows.

Melissa: Awakenings is such a wonderful title. The body grows, changes, breaks, and fails; meanwhile and nevertheless, it awakens, morning after morning and in myriad metaphorical ways, as well. How did this title come about, Diane, and how do you think it encapsulates the anthology’s essays?

Diane: Ariana D. Den Bleyker, the wonderous force behind ELJ Editions (and Emerge Literary Journal), came up with Awakenings: Stories of Body & Consciousness. I absolutely love the title! It reflects a spirit and energy I’ve been noticing more and more regarding bodies and owning and sharing the stories we have about them. Many people are pushing back hard against all the noise and the very real consequences of intolerance. They are rejecting the notion that the body must look/work/love in any one specific way. People are speaking, moving—and writing—so courageously in this world, awakened to the truth and beauty that we and our bodies hold and awakening those who are not quite there yet. It is not easy to write so openly and vulnerably and put yourself and your truth out there for others to read. That’s one of the things I most admire about the essays in the collection—the fearlessness of the contributors, or, rather, the determination to speak truth in spite of any fear they may have.

Melissa: While reading Awakenings, I frequently found myself recollecting this sentence from Gayle Brandeis’s foreword: “Hope and liberation bloom through this anthology, often culminating in hard-won self-love.” What kinds of paths toward self-love do these pieces illuminate? If self-love is indeed hard-won, why is that, do you think? Who and what do we battle to win this acceptance and cherishing of the self?

Diane: Self-love is often hard-won, especially when you do not fit the image of who or what society loves and values; so many of us, from the time we were tiny, were told the ways in which we were lacking. We battle voices around us that tell us we are not fitting that gender image, that racial role, that age, class, size ideal. We’re not who we “should” be or “should” aspire to become. Unfortunately, many of us have internalized those voices and adopted them as our own. Ugh!!! Until we put those voice to bed, until, as Aria Dominguez says in her beautiful “The Light in Him,” we accept the light in ourselves, self-love will continue to be a great challenge.

Several of the pieces in the book deal with abuse and speak to the healing they found after breaking the silence and in seeking and finding allies. That’s one powerful path. Ezekiel Cork in “Right as Rain” and Marion Dane Bauer in “What I Knew” had to discover who they were at their core before they could fully love themselves. Ellen Birkett Morris found meditation; Jane Palmer documented her long road with tattoos; Sandell Morse looked to her heritage. I am deeply inspired by the many different paths the contributors have taken to come to a place where they can cherish themselves. Such wise and wonderful models they are for us all.

Melissa: In your introduction, you note, “Weight is a heavy word for so many of us,” and this made me think about how irrevocably the body is tied to size, something that can be measured, charted, ranked, and assessed. The essay “The Light in Him” addresses this powerfully, especially toward the end: “I am overcome by sadness at how the others looked at him as if he were not even human. As if his more-ness made him lesser.” This “more-ness” is later echoed in “The Gallbladder Monologues” with the line, “Too wide too fat too loud too aggressive too assertive too unpredictable.” These essays, as well as a few of the others, invite us to reflect on the criticism that stems from a perceived too-muchness and deviation from a hazy Goldilocks standard of just-right. Your introduction mines this further when you point out, “Our bodies’ worth—our human worth—is placed on many different scales.” What scales do these essays reveal? And what means of defiance and subversion do the essays offer?

Diane: Judging our worth (or lack thereof) by the number on bathroom scale! That ritual is so familiar to too many of us—and the implications of our literal weight is discussed so elegantly in those pieces you mentioned and in all the essays in the section “Taking Up Space.” But there are other scales and judgments that are just as toxic. Camille U. Adams writes about being judged for eating the foods her body needs! Barb Mayes Boustead writes about being judged for experiencing physical pain. Claude Olson for their height. Eleonora Balsano for her hair color. Kelli Short Borges for the shape of her rear! These essays push back against those judgments. They say ENOUGH and NO and I AM NOT PLAYING by those rules anymore! That is the defiance and subversion these essays so powerfully offer!

Melissa: From the beginning to the end of this anthology, there are questions raised and answers offered. For instance, while certain pieces, like “Lip Service,” explore the ways we punish our bodies (and how society pressures us to pursue this punitive course), others, like “The Body Knows” and “The Question Body,” show how we can heal the wounds incurred through this learned self-hatred. The anthology essays admirably “speak” to one another, and that reveals such editorial mastery on your part, Diane. Tell me about your process of selecting, categorizing, and organizing these works. Were you mindful of certain overarching principles, purposes, or goals?

Diane: Thank you for those kind words, dear Melissa! My goals for the anthology were simple and ones of which I was mindful throughout the entire process: to bring together diverse stories that spoke to the hard and joyous truths of the body, stories that would move people, that would, hopefully, help readers to see their own bodies and body experiences in a new light and with greater compassion, appreciation, love, and hope. We received so many wonderful submissions. Selecting pieces was a difficult task. I am incredibly grateful to all who submitted and trusted us with their words. There was such a wide range of voices and body experiences to savor. I printed out all the subs, laid them out on my couch, my coffee table, the floor, and made piles—lots and lots of piles. I carried those piles with me throughout the house, reading, rereading, writing notes on the pages, making decisions. Soon, there were fewer piles, and the ones left did seem to speak to each other: “Hi. I hear you,” some said to others. “Yes. This is how I see it.” “Wow. I thought I was the only one.” The pieces gravitated toward each other and formed themselves into little pods. I feel like I just found names for the different sections.

Melissa: One thing many of these pieces made me think about was how tangibly our bodies anchor us to our families. We can sometimes actually trace from whom a specific feature comes. But not all bequests are visible or obvious. How do these pieces also suggest subtler inheritances? What are some of the body-related values, beliefs, and convictions parents pass down?

Diane: Oh families, families, families! Most family members do the best they can. And/but the hurts and the negative messaging are often passed down through generation after generation like Great Grandma’s old, chipped dish that we simply can’t bear to get rid of. This is true of damaging body-related values and misguided beliefs of all kinds.

Not all our inherited messages are toxic, thankfully! I’m thinking of your own gorgeous contribution to the anthology, “Just Hair,” and the tenderness with which you recount your mother’s unusual ritual of adding family hair-clippings to her garden, the physical resemblance between you and your mother, the three-generational connection—your mom, you, your daughter—around hair. I think of “Don’t Lie to Me,” in which Lizz Schumer writes of her passion for words—accurate words—and her disdain for sugar-coating and fairy-taling of necessary truths. This she got from her mother who “didn’t go in for the cutesy euphemisms most parents teach their children for their private parts and didn’t dumb down the answers to our questions about how our bodies worked.” I think of the deeply moving “Perfect” by Maggie Pahos and how she carries her mother’s and her own imperfect perfections so bravely and beautifully.

Melissa: This anthology makes me feel so many feelings, most especially, though: tenderness. It makes me feel tender toward others’ taxed, tempted, ever-changing, frequently-failing, persistently-judged bodies. It makes me feel tender toward my own. How did this anthology make you feel as you were curating it, Diane? And when you read it now that it’s completed, does it elicit a different feeling?

Diane: Tenderness is a wonderful word to describe how I felt while curating the anthology and how I feel about the anthology now. The essays brought out joy and wonder, sadness too. While curating and especially now that these glorious essays are sitting side by side in one collection, I am struck by the fierce respect and admiration I feel for these beautiful brave voices, by the gratitude that lives in my every cell, and by the hope I have that Awakenings will reach many eyes and hearts and will awaken a deeper sense of self-acceptance and compassion in all who spend time with it.